HISTORY

The Beginnings

The history of the place

The hotel building

Lamp annunciator

Telephones and other devices

The Grand Hôtel Steiner

In the 1920s Prague went through huge changes. From a sleepy provincial Austro-Hungarian town it became a modern city and the capital of independent Czechoslovakia. That caused many problems, including a marginal one: where to accommodate government delegations and other important guests coming to Prague. Yes, Prague didn’t have enough modern hotels.

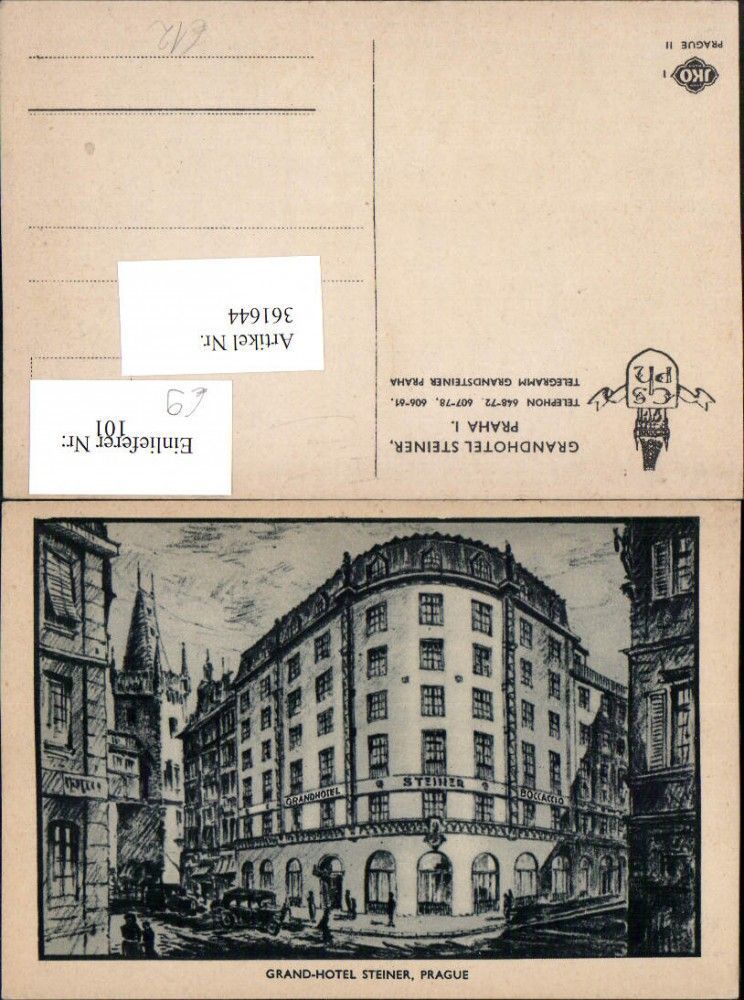

A resolute response to this deficiency came from Mr. Josef Steiner who bought a plot of land next to the Municipal House (Obecní dům) in order to build a modern hotel. In doing so he used his rich experience from abroad, namely from England and Switzerland. He approached architect František Malypetr and other experts, who created an exclusive European-class hotel building. The Grand Hôtel Steiner was opened on 25 February 1927.

The oldest reference to house no. 652 comes from 1406. At the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War (in 1623) the house was confiscated from its owner, Jan Sekerka of Sedčice. It was a punishment for his participation in the Estate Revolt against Emperor Ferdinand II. Although the house often changed owners during the following centuries, it was still called U sekerek (At the Hatchets; “sekerka” meaning “hatchet”).

In the 19th century it became a tavern called U tří sekyrek (At Three Hatchets), which ceased to exist along with the surrounding buildings during Prague’s redevelopment at the end of the 19th / beginning of the 20th century. In spite of that it can be seen, with almost the whole historical centre of Prague, in Langweil’s unique mid-19th-century model of Prague which can be found at the City of Prague Museum, 10 minutes away from the hotel.

Josef Steiner brought to Prague many conveniences which were not commonly found at other hotels of that time. The hotel building alone was unparalleled in Prague. A special construction was used consisting of riveted iron columns, which made it possible to leave out central supporting walls and, as a result, save space in the interior.

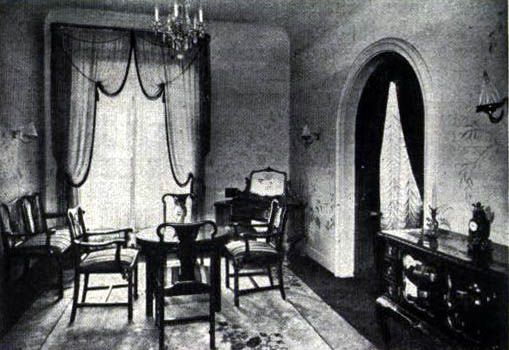

The six-storey hotel had 100 rooms, many of which could be joined into an above-standard suite with a lounge, bedroom, private dining room and bathroom. Most rooms had their own bathroom, which, in the more luxurious once, included a bath and bidet. A newspaper article announcing the opening of the new Prague hotel regarded even running water (both cold and hot) in the rooms as worth mentioning. Apart from that, the rooms also had built-in wardrobes.

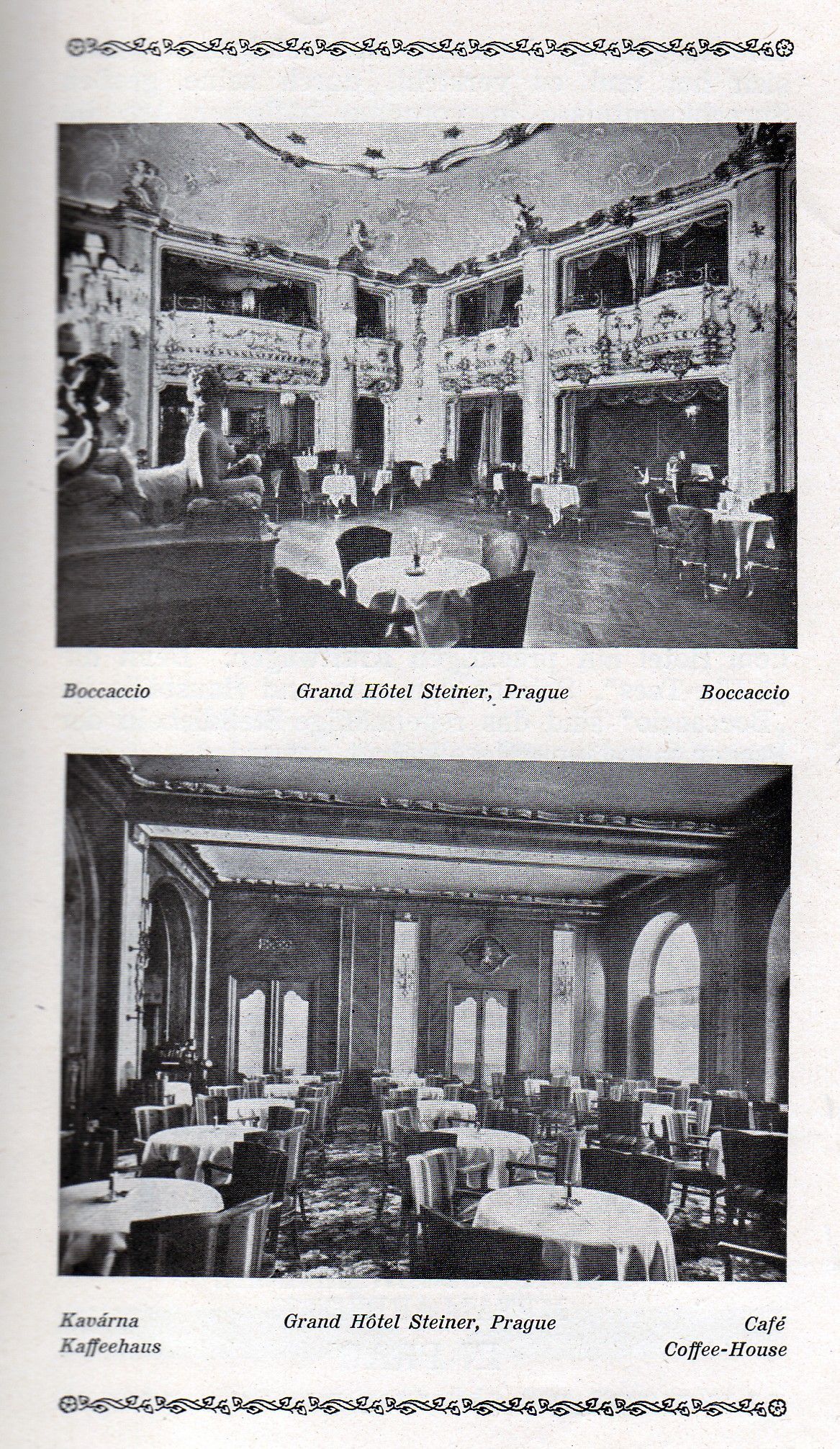

Hotel guests could also use garages, which was far from usual at that time. A beautiful Rococo revival dancing hall, called the Boccaccio, was created in the basement. There were two terraces on the hotel’s upper floors – one was open and oriented towards Celetná street, while the other had a hanging sunroom.

A lamp annunciator was used as an original way to call room service. At that time bells were usually used at hotels. However, they were not only disturbing but also inaccurate. The attendant first had to look who was calling but even then a mistake could be made. The Grand Hôtel Steiner used a different system.

A button was pushed in the room and indicators came on above its door, on the direction indicator in the hall, on the room service panel as well as on the control panels in corridors. As a result, error rate was eliminated and the signalling didn’t disturb anybody. After coming into the room, the attendant would turn off the indicators by pushing a button.

The whole action was followed on a control panel by the receptionist, who got a perfect idea of the attendant’s speed. The system also included portable buzzers carried by the chambermaids. The buzzer was plugged in while the room was being cleaned and if a guest called, the maid was notified by its sound and could find the guest quickly, being assisted by the routing system described above.

Another technical improvement was private telephones in rooms which could be used without having to call the reception first. Mr. Steiner left nothing to chance, which is why he had two accumulators placed in the yard to supply power in case of emergency. That way, a trouble-free operation of the annunciator and of the entry phone was ensured. Apart from that, the hotel had its own transformer in the basement.

Electricity powered 5 lifts: one was used by guests, two would transport food, another one would transport clothes (to reduce the load on the cloakroom) and one was used for supplies.

The room service also used a central vacuum cleaner.

Although the Boccaccio Ballroom was built in a Rococo revival style and is adorned with lavish stucco decoration, gilt elements and traditional Czech crystal, in its own time it was a very modern place, deliberately separated from the main hotel building so that the hotel guests were not disturbed. It has a separate staircase and entrance hall, which could be entered from the café. The smoky air was conducted away from the basement hall by an efficient air-conditioning system, at the same time supplying fresh air, which was heated in winter.

The Boccaccio Ballroom is the only part of Grandhotel Bohemia that has been preserved in its original form. It is situated in the basement and you can visit it, too. It will take you back to the carefree 1920s, when couples danced on the marble floor to the rhythm of tango. A newspaper report of that period describes the Boccaccio as an “intimate and aristocratic hall,” which “irresistibly tempts you to dance.”

It is no wonder that this work of art consisting of artificial marble, gold and crystal glass and decorated with unique details immediately became one of the places most frequently visited by the cream of Prague’s society. Five O’Clock Tea Parties and Dance Nights (Soirée dansantes) were held every day and the guests who came to have fun included important persons, such as the Foreign Minister, Jan Masaryk, the U.S. Ambassador to Prague and many others. It is said that the whole Masaryk family (including Tomáš G. Masaryk, the first president of Czechoslovakia) had the large box above the bar reserved, which is why it is still called the Presidential Box.

In the afternoons, ladies would come to introduce their daughters to the society and look for potential husbands for them. Later in the evenings and at nights the Boccaccio would change into a luxurious nightclub for men. Business would be done, politics discussed and friends made in the company of beautiful women, while Cuban cigars were smoked and sparkling wine drunk. Welcome to the golden era of the Grand Hôtel Steiner.

The Grand Hôtel Steiner also spent a great deal of money on other furnishings, such as carpets, parquet floors, wall lining, etc. The bathrooms were furnished with original English faience washbasins and tiled with marble, and most of the interior was wallpapered where polished wood was not used. For example, the French restaurant was panelled with lemon tree wood, the main café with Caucasian cherry and the smaller café with inlaid cherry. Besides that, the interior was adorned with first-class china and carved and gilt elements. In the hotel hall there was a fireplace.

However, the true gem and demonstration of luxury (maybe almost sumptuous) was and fortunately still remains to be the Boccaccio Ballroom.

At that time the hotel’s chef was Josef Bittermann. He stayed for a long 25 years, during which he also published his famous Big Cookery Lexicon. Since it first came out in 1939, it has not only been reprinted many times, but it was used as a basis of textbooks for cook apprentices as late as in the 1960s.

Modern and luxurious

Boccaccio Ballroom

Josef Bittermann

Hotel Praha

The Grand Hôtel Steiner survived WWII without any harm, but the arrival of the Communists ended its golden era abruptly. Ironically, the Communists seized power in Czechoslovakia on 25 February 1948, i.e. on the very day of the 21st anniversary of the hotel’s opening.

Its owner and founder, Josef Steiner, decided to offer his Prague hotel to the Czechoslovak Communist Party for official purposes under the condition that his family would be allowed to stay at least as employees of the hotel because all private enterprises had been nationalised and private business banned. Mr. Steiner probably hoped (like many others) that the rule of the Communist Party wouldn’t last long and wanted to make sure his family had some control of the hotel.

Unfortunately, he was wrong. His tracks were lost during the 40 dark years and so were the beauty and luxury of the hotel, which was renamed Hotel Praha. It was inaccessible to the public because for a long 40 years it became the main provider of catering services for the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. It couldn’t be found in any guidebooks, wasn’t referred to by any tourist information offices and wasn’t even listed in the phone book. It was only used by the Communist Party.

The original equipment and furnishings disappeared and were sold and the rooms were equipped with new “modern” unit furniture and fitted with eavesdropping devices because the hotel was used for accommodating as well as eavesdropping on Communist officials and for collecting compromising information. Wild parties for Communist Party officials and foreign guests were given in the Boccaccio ballroom. They were probably really wild because during the 1993 reconstruction, bullets from a pistol were found in the ceiling.

In the 1970s the Grand Hotel from the First Czechoslovak Republic era was in such a condition that it was no longer possible to accommodate official delegations in it, so only unofficial and maybe even illegal guests would stay there. In another part of Prague, a new Hotel Praha was built, which was supposed to be used as the Communist Party’s official hotel.

Because the Central Committee of the Communist Party was a supreme state authority, besides providing catering services during different official visits, the hotel had to run the holiday resorts of the new state aristocracy which were situated outside Prague, including the presidential summer residence in Lány. However, the most important events took place at Prague Castle and the Hotel Praha provided complete catering services for them. These events included Czechoslovak presidents’ inaugural lunches as well as the visits of the leading representatives of foreign countries, especially of those belonging to the socialist bloc.

However, in terms of professional skills it was a blessing in disguise. Top-class experts with experience from pre-war hotels and restaurants were concentrated at the hotel. As a result, the training of apprentices, who began to come in the 1960s to get more experience, was at a very high level. In fact, many of those trainees are now respected professionals in the hotel and restaurant business.

A certain change happened at the beginning of the 1980s, when the new Hotel Praha was opened in Prague 6. It was also inaccessible to the public and was used solely for the accommodation of the government’s guests and for different government events. Some of the employees were transferred to the new hotel. The old Hotel Praha started to be used as a facility for the suites of government delegations, while VIP guests would be accommodated at the new hotel. Interestingly, the new Hotel Praha doesn’t exist anymore as it was demolished by its owner in 2015. Thus, the Steiner / Praha / Bohemia Hotel survived not only the Communist era but also its successor.

The Rococo revival Boccaccio Ballroom in the hotel’s basement has repeatedly been used by film-makers. In the popular film, Angel in a Devil’s Body (1983), it even briefly returned to the time of its greatest glory, i.e. the pre-war era, when the cream of society would meet in its cabaret.

Several Czech films made in the Boccaccio remind us of those times. The Boccaccio Hall was often used as a filming location during the Communist times. It made such a lavish impression that it perfectly matched the Communist idea of a “capitalist hellhole.” Czech film fans will certainly remember Angel in a Devil’s Body or The Angel Seducing the Devil, but the hall can also be seen in some of the episodes of The Sinful People of Prague and in one of the Thirty Cases of Major Zeman.

Catering for government delegations; Lány

Decline

The new Hotel Praha

Film-makers

Grand Hotel Bohemia

Restoration

The hotel’s names and owners

The 1989 Velvet Revolution saved the Grand Hotel from destruction. It was returned to the Steiner family, who sold it to Austria Hotels. The hotel went through significant repair, was newly furnished and in a mere eleven months it was re-opened on 1 October 1993 bearing its present name, The Grand Hotel Bohemia.

Nowadays, this five-star hotel provides accommodation in 79 air-conditioned luxury rooms on eight floors and it can be found again in most guidebooks. It became a member of Gerstner Imperial Hotels & Residences as one of the Group’s eight hotels situated in Austria and the Czech Republic.

In 1993 Boccaccio Ballroom was completely reconstructed so that it regained its previous beauty. The artificial marble was repaired, the wall decorations and paintings were restored and re-guilt, the sculptures of cupids holding musical instruments or arrows were carefully restored as well, and mirrors and lamps were replaced. Despite its appalling condition before the reconstruction, part of the original decoration was preserved.

As a result we can now admire the original parquet floor comprised of wooden panels, each of them consisting of nine kinds of Oriental wood. The time and thousands of pairs of dancing shoes have made the wood so hard that it survived even the disastrous flood in 2002, when the hall’s floor was covered by a one-metre layer of murky water and mud for three days. The floor is laid on a wooden grid so that it is flexible and doesn’t make the dancers’ feet sore, and as a result guests can stay for one more drink.

The central chandelier was also salvaged – during the reconstruction it was taken down and all its 4,000 hand-made pieces were carefully cleaned and hung again, so now you can admire its glittering beauty.

Today, Boccaccio remains to be one of the most interesting halls in Prague. It frequently hosts different parties and wedding receptions as well as seminars and conferences. It is no longer used for its original purpose (i.e. as a dance hall, night club and restaurant) but it is definitely as beautiful as on the day when Mr. Steiner opened it to the public.

- The Grand-Hôtel Steiner (owned by Josef Steiner, 1927–48)

- Hotel Praha (owned by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, 1948–93)

- Grandhotel Bohemia (owned by Gerstner Imperial Hotels & Residences, 1993–present)

GRAND HOTEL BOHEMIA

Králodvorská 652/4

110 00 Praha 1

Czech Republic

Tel: +420 234 608 111

Email: office@grandhotelbohemia.cz

USEFUL INFORMATIONS

All Rights Reserved | Grand Hotel Bohemia Prague